The field of audio isolation has moved beyond simple, mass-loaded materials like heavy steel or dense rubber to embrace advanced composite materials that utilize internal structure and chemical engineering to actively dissipate kinetic energy. Innovations such as microcell rigid foam represent a paradigm shift, achieving significantly higher damping coefficients and superior performance across a broader frequency spectrum while drastically reducing weight and cost compared to older, passive isolation techniques.

The Limitations of Passive Damping

Traditional vibration control relied heavily on two passive methods that have inherent limitations:

- High Mass: Using extremely heavy materials (e.g., granite slabs, lead) to increase inertia. This shifts the resonant frequency but doesn’t eliminate the energy; it merely makes the system more resistant to external forces.

- Simple Elastomers: Using basic rubber or sorbothane pads. These act like a spring and damper, but often exhibit a “rebound” effect, storing and releasing energy, which can muddy the soundstage or introduce their own resonant characteristics.

Microcell Technology: The Active Damping Revolution

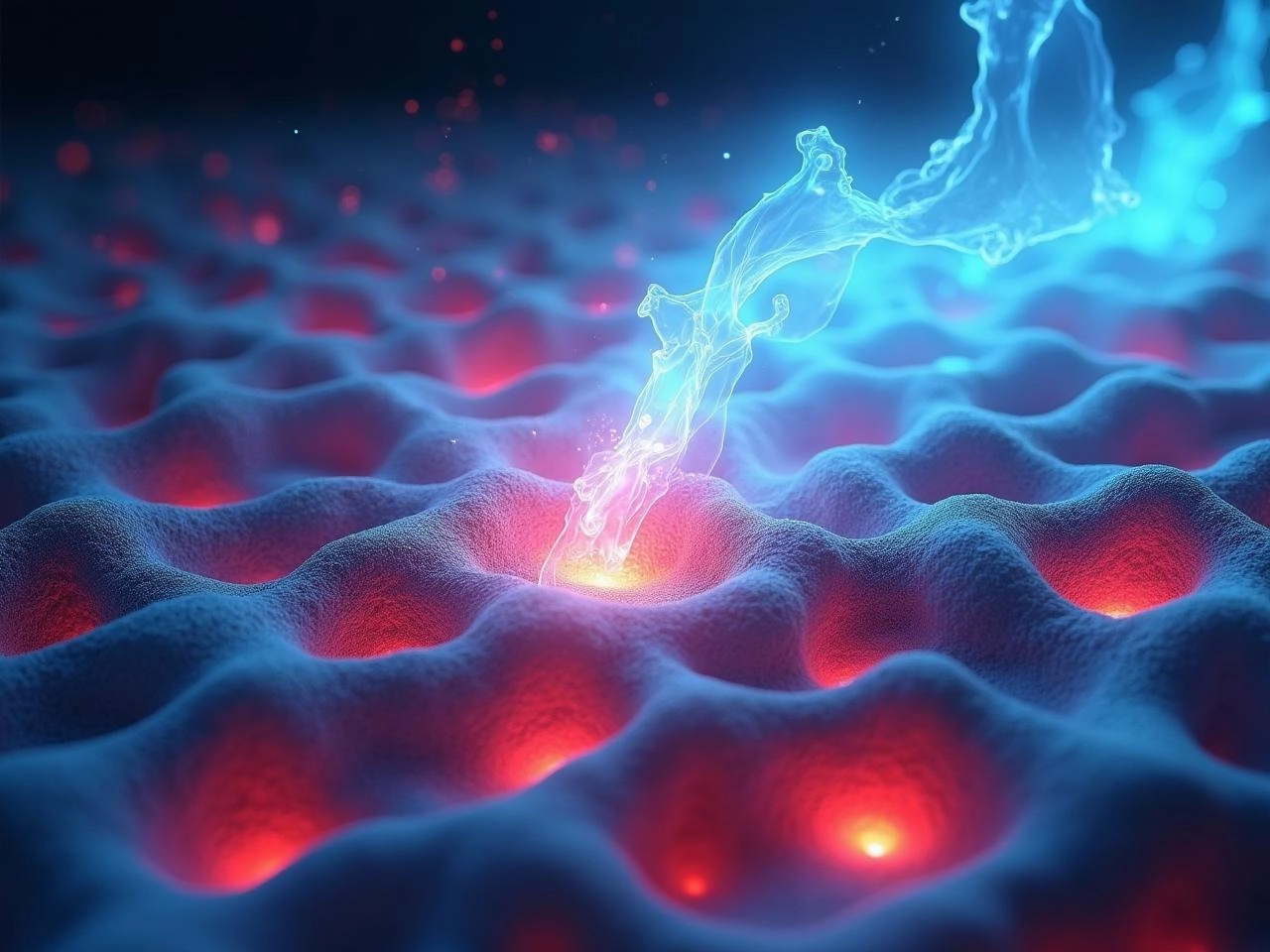

Modern composite materials are engineered at a microscopic level to be active participants in the energy conversion process. The core innovation lies in structure, not just density.

- The Microcell Matrix: Composites like microcell rigid foam (e.g., PVC matrix) are composed of an interconnected network of uniform, sealed gas bubbles.

- The Dissipation Mechanism: When a vibration wave passes through, the internal walls of these microscopic cells undergo constant deformation. This rapid internal friction and flexing convert the vibrational (kinetic) energy directly into infinitesimal amounts of heat, a process known as viscoelastic damping.

- Performance Metrics: This approach provides a high damping ratio—the speed at which a material settles after a vibration—leading to a fast, clean, and uncolored audio presentation.

Comparison: Engineered Composites vs. Traditional Materials

| Material Type | Vibration Control Strategy | Primary Limitation |

| Microcell Foam | Viscoelastic Damping (Energy Conversion) | Requires correct component load distribution |

| Sorbothane/Rubber | Isolation (Spring/Damping) | Can exhibit rebound or compression set |

| Granite/Steel | Inertia (Mass Loading) | Shifts resonance, does not eliminate energy |

| Air Bladders | Pneumatic Decoupling | Can be unstable, requires complex setup/maintenance |

The Future of Materials: Integration and Lightness

Current research is focused on creating lighter, more efficient composites. The goal is to maximize the damping coefficient while minimizing material volume. This allows for aesthetically pleasing, low-profile designs—like the precision-engineered footers and foundations—that fit seamlessly into high-end audio setups without requiring bulky, heavy isolation racks.

Q&A: Material Science and Audio

Q: How does the material choice affect different frequencies? A: Density and stiffness primarily affect low-frequency damping, while internal micro-structures (like in microcell composites) are highly effective at absorbing mid-to-high frequency mechanical ringing. A balanced material must address both.

Q: Is a material with a high coefficient of friction a good isolator? A: Not necessarily. High friction (stickiness) helps stop movement between surfaces, but the key to isolation is internal damping—converting the energy within the material—rather than relying on surface adhesion.